9

Силантьев

В.Б.

Основные микроэкономические модели-формулы и пояснения к ним

-

qD = qD(P, Pk, Ps, I,

Ts, τ, n); -

qS = qS(P, PR, TC, Th, Tx, τ, n);

-

qD = qS = qe; PD = PS

= Pe; -

Pe∫PdmaxqD(P)dP =

Psmin∫PeqS(P)dP; -

EDP = Δq/q∙ΔP/P = Δq/ΔP∙P/q; EDP

= dq(P)/dP∙ P/q; -

EDI = Δq/q∙ΔI/I = Δq/ΔI∙I/q; EDI

= dq(I)/dI∙ I/q; -

EDiPj = Δqi/qi∙ΔPj/Pj

= Δqi/ΔPj∙Pi/qj;

EDiPj = dqi(Pj)/dPj∙

Pj/qi; -

TU = TU(qA, qB), например, TU =

AqαAqβB; если А =

α = β = 1, то qA = TU/qB, тогда при ТU = Const –

семейство гипербол – кривых безразличия; -

MUA = ∂TU/∂qA; MUB = ∂TU/∂qВ;

-

ТР = TP(K, N), например, TP = AKαNβ,

откуда Kα = TP/ANβ, и при TР =

Const – семейство гипербол – изоквант; -

MРК = ∂TP/∂K; MPN = ∂TP/∂N;

-

MPK∙P = MRPK; MPL∙P =MRPL;

-

I = PAqA + PBqB, при

I = Const, семейство прямых с отрицательным

наклоном вида: qA = I/PA −

PВ/PAqB; -

TC = rK + wL, при ТС =Const, cемейство прямых с

отрицательным наклоном вида: К =TC/r −

w/rN; -

MRSAB = MUA/MUB = PA/PB,

откуда MUA/PA = MUB/PB

= λ;

-

MUA = λPA; MUB = λPB;

MUi = λPi; -

MRTSKL = − dL/dK = MRPK/MRPL = r/w, откуда

MRPK/r = MRPL/w = 1; -

MRPK = r; MRPL = w; MR = MC;

-

TFC = AFC∙Q = TC – TVC;

-

AFC = TFC/Q = ATC – AVC;

-

MFC=0, т.к. FC = Const;

-

TVC = AVC∙Q = TC – TFC;

-

AVC = TVC/Q = ATC – AFC;

-

MC = MVC = dTVC/Dq = AVCmin;

-

TC = TFC + TVC = (AFC+AVC)Q;

-

TC = TC/Q = AFC+AVC;

-

MC = MTC = dTC/dq = ATCmin;

-

TC = ∫MC(q)dq + FC;

-

π(q) = TR(q) – TC(q); π(q) → max

при dπ(q)/dq = 0 = dTR(q)/dq – dTC(q)/dq, откуда следует

условие MR = MC;

-

MR = MC = P = ATCmin;

-

MR = MC = P = AVCmin;

-

MR = MC < Pm > ATCmin;

-

E-1 = (Pm – MC)∙Pm-1;

-

πm = TR/E;

-

PDV = 1/(1 + i)n;

-

NPV = [π1/(1 + i) +

π2/(1 + i)2 + … +

πn/(1 + i)n] — I; -

MRTP = − dC2/dC1

= (1 + I); -

MRSAXY = MRSBXY;

-

MRTSXKL = MRTSYKL;

-

MRPTXY = MRSAXY = MRSBXY.

Глоссарий микроэкономико-математических терминов

P –

цена

Pk–

цена дополняющих (комплементарных)

товаров и услуг

Ps

– цена замещающих (субститутных) товаров

и услуг

Pe

– цена равновесия

Pdmax

– максимальная цена спроса

Psmin

– минимальльная цена предложения

Pm

– цена монопольная

π

– прибыль

D –

спрос (характер спроса)

S –

предложение (характер предложения)

E –

эластичность

I –

доход

Ts

– вкусы, предпочтения

Tx

– налоги

Th

– технологии

TU

– полная полезность

МU –

предельная полезность

MRS –

предельная норма замещения

MRTS

– предельная норма технического

замещения

ТР

– полный продукт (полная производительность)

АР

– средний продукт (средняя

производительность)

MU –

предельный продукт (предельная

производительность)

ТС –

полные издержки

МС –

предельные издержки

АС

– средние издержки

FC

– постоянные издержки

VC

– переменные издержки

TR

– полная выручка

MR

– предельная выручка

MRP –

предельный продукт в денежной форме

К

– капитал

L

– труд

N – количество потребителей и/или

покупателей (продавцов и/или производителей)

R – ресурсы (или – из контекста – рента,

процент, норма, степень)

τ – земля, природно-климатические

условия и/или естественные факторы

производства

qD – величина (количественная

характеристика) спроса

qS– величина (количественная

характеристика) предложения

λ – предельная полезность денег

r – цена капитала (реальная ставка

процента)

w – цена труда (реальная часовая тарифная

ставка заработной платы)

d – дифференциал (полная производная

функции)

∂ – дифференциал (частная производная

функции)

α – эластичность производственной

функции по затратам капитала

β – эластичность

производственной функции по затратам

труда

PDV

– текущая дисконтированная

(приведенная) стоимость

FDV

– будущая дисконтированная

(приведенная) стоимость

i – норма

дисконтирования (приведения затрат к

единому моменту времени)

n – число лет (номер последнего

года) в периоде дисконтирования

NPV

– чистая дисконтированная

стоимость

πn

прибыль, получаемая в n-м

году

I

– инвестиции

MRTP

– предельная норма

временного предпочтения

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In economics, the marginal product of capital (MPK) is the additional production that a firm experiences when it adds an extra unit of capital.[1] It is a feature of the production function, alongside the labour input.

Definition[edit]

The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the additional output resulting, ceteris paribus («all things being equal»), from the use of an additional unit of physical capital, such as machines or buildings used by businesses.

The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the amount of extra output the firm gets from an extra unit of capital, holding the amount of labor constant:

Thus, the marginal product of capital is the difference between the amount of output produced with K + 1 units of capital and that produced with only K units of capital.[2]

Determining marginal product of capital is essential when a firm is debating on whether or not to invest on the additional unit of capital. The decision of increasing the production is only beneficial if the MPK is higher than the cost of capital of each additional unit. Otherwise, if the cost of capital is higher, the firm will be losing profit when adding extra units of physical capital.[3] This concept equals the reciprocal of the incremental capital-output ratio. Mathematically, it is the partial derivative of the production function with respect to capital. If production output

Diminishing marginal returns[edit]

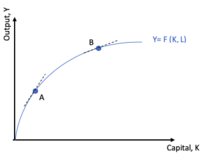

One of the key assumptions in economics is diminishing returns, that is the marginal product of capital is positive but decreasing in the level of capital stock, or mathematically

Output as a function of capital input

Graphically, this evidence can be observed by the curve shown on the graphic, which represents the effect of capital, K, on the output, Y. If the quantity of labor input, L, is hold fixed, the slope of the curve at any point resemble the marginal product of capital. In a low quantity of capital, such as point A, the slope is steeper than in point B, due to diminishing returns of capital. By other words, the additional unit of capital has diminishing productivity, once the increase on production becomes less and less significant, as K rises.[4]

Example[edit]

Consider a furniture firm, in which labour input, that is, the number of employees is given as fixed, and capital input is translated in the number of machines of one of its factories. If the firm has no machines, it would produce zero furnitures. If there is one machine in the factory, sixteen furnitures would be produced. When there are two machines, twenty eight furnitures are built. However, as the number of machines available increase, the change in the output turns out to be less significant compared to the previous number. That fact can be observed in the marginal product which begins to decrease: diminishing marginal returns. This is justified by the fact that there is not enough employees to work with the extra machines, so the value that these additional units bring to the company, in terms of output generated, starts to decrease.

| Number of machines | Output (Furnitures produced per day) | Marginal Product of Capital |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 16 | 16 |

| 2 | 28 | 12 |

| 3 | 39 | 11 |

| 4 | 46 | 7 |

| 5 | 49 | 3 |

| 6 | 50 | 1 |

Rental rate of capital[edit]

In a perfectly competitive market, a firm will continue to add capital until the point where MPK is equal to the rental rate of capital, which is called equilibrium point. This fact justifies why in perfectly competitive capital markets, the price of capital can be seen as the rental rate.[5] The price of capital is determined in the capital market by the respective capital demand and supply.

The marginal product of capital determines the real rental price of capital. The real interest rate, the depreciation rate, and the relative price of capital goods determine the cost of capital. According to the neoclassical model, firms invest if the rental price is greater than the cost of capital, and they disinvest if the rental price is less than the cost of capital.[2]

MRPK, MCK and profit maximization[edit]

It is only profitable for a firm to keep adding capital when the marginal revenue product of capital, MRPK (the change in total revenue, when there is a unit change of capital input, ∆TR/∆K) is higher than the marginal cost of capital, MCK (marginal cost of obtaining and utilizing a machine, for example). Thus, the profit of the firm will reach its maximum point when MRPK = MCK.

See also[edit]

- Marginal product of labor

- Production theory basics

- Marginal efficiency of capital

References[edit]

- ^ «What is Marginal Product of Capital?». My Accounting Course.

- ^ a b N. Gregory Mankiw. (2010). Macroeconomics. United States: Worth Publishers

- ^ «Marginal product of Capital». XPLAIND. Obaidullah Jan.

- ^ Intermediate Macroeconomics (First ed.). Robert J. Barro. 2017. ISBN 9781473725096.

- ^ «Rental rate». Boundless.

Sources[edit]

- Nicholson, Walter (1978). Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions (2nd ed.). Hinsdale: Dryden Press. pp. 182–188. ISBN 0-03-020831-9.

- Robinson, R. Clark. «Marginal product of labor and capital» (PDF). Northwestern University Class Handout. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2006.

In economics, the marginal product of capital (MPK) is the additional production that a firm experiences when it adds an extra unit of capital.[1] It is a feature of the production function, alongside the labour input.

DefinitionEdit

The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the additional output resulting, ceteris paribus («all things being equal»), from the use of an additional unit of physical capital, such as machines or buildings used by businesses.

The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the amount of extra output the firm gets from an extra unit of capital, holding the amount of labor constant:

Thus, the marginal product of capital is the difference between the amount of output produced with K + 1 units of capital and that produced with only K units of capital.[2]

Determining marginal product of capital is essential when a firm is debating on whether or not to invest on the additional unit of capital. The decision of increasing the production is only beneficial if the MPK is higher than the cost of capital of each additional unit. Otherwise, if the cost of capital is higher, the firm will be losing profit when adding extra units of physical capital.[3] This concept equals the reciprocal of the incremental capital-output ratio. Mathematically, it is the partial derivative of the production function with respect to capital. If production output , then

Diminishing marginal returnsEdit

One of the key assumptions in economics is diminishing returns, that is the marginal product of capital is positive but decreasing in the level of capital stock, or mathematically

Output as a function of capital input

Graphically, this evidence can be observed by the curve shown on the graphic, which represents the effect of capital, K, on the output, Y. If the quantity of labor input, L, is hold fixed, the slope of the curve at any point resemble the marginal product of capital. In a low quantity of capital, such as point A, the slope is steeper than in point B, due to diminishing returns of capital. By other words, the additional unit of capital has diminishing productivity, once the increase on production becomes less and less significant, as K rises.[4]

ExampleEdit

Consider a furniture firm, in which labour input, that is, the number of employees is given as fixed, and capital input is translated in the number of machines of one of its factories. If the firm has no machines, it would produce zero furnitures. If there is one machine in the factory, sixteen furnitures would be produced. When there are two machines, twenty eight furnitures are built. However, as the number of machines available increase, the change in the output turns out to be less significant compared to the previous number. That fact can be observed in the marginal product which begins to decrease: diminishing marginal returns. This is justified by the fact that there is not enough employees to work with the extra machines, so the value that these additional units bring to the company, in terms of output generated, starts to decrease.

| Number of machines | Output (Furnitures produced per day) | Marginal Product of Capital |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 16 | 16 |

| 2 | 28 | 12 |

| 3 | 39 | 11 |

| 4 | 46 | 7 |

| 5 | 49 | 3 |

| 6 | 50 | 1 |

Rental rate of capitalEdit

In a perfectly competitive market, a firm will continue to add capital until the point where MPK is equal to the rental rate of capital, which is called equilibrium point. This fact justifies why in perfectly competitive capital markets, the price of capital can be seen as the rental rate.[5] The price of capital is determined in the capital market by the respective capital demand and supply.

The marginal product of capital determines the real rental price of capital. The real interest rate, the depreciation rate, and the relative price of capital goods determine the cost of capital. According to the neoclassical model, firms invest if the rental price is greater than the cost of capital, and they disinvest if the rental price is less than the cost of capital.[2]

MRPK, MCK and profit maximizationEdit

It is only profitable for a firm to keep adding capital when the marginal revenue product of capital, MRPK (the change in total revenue, when there is a unit change of capital input, ∆TR/∆K) is higher than the marginal cost of capital, MCK (marginal cost of obtaining and utilizing a machine, for example). Thus, the profit of the firm will reach its maximum point when MRPK = MCK.

See alsoEdit

- Marginal product of labor

- Production theory basics

- Marginal efficiency of capital

ReferencesEdit

- ^ «What is Marginal Product of Capital?». My Accounting Course.

- ^ a b N. Gregory Mankiw. (2010). Macroeconomics. United States: Worth Publishers

- ^ «Marginal product of Capital». XPLAIND. Obaidullah Jan.

- ^ Intermediate Macroeconomics (First ed.). Robert J. Barro. 2017. ISBN 9781473725096.

- ^ «Rental rate». Boundless.

SourcesEdit

- Nicholson, Walter (1978). Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions (2nd ed.). Hinsdale: Dryden Press. pp. 182–188. ISBN 0-03-020831-9.

- Robinson, R. Clark. «Marginal product of labor and capital» (PDF). Northwestern University Class Handout. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2006.

Предельный продукт капитала: понятие, формулы, пример и график

На чтение 3 мин Просмотров 874 Опубликовано 16.05.2020

Предельный продукт капитала (MPK) – это прирост общего объема производства, возникающее в результате увеличения капитала на одну единицу при сохранении неизменности всех остальных факторов производства.

Фирмы принимают инвестиционные решения, сравнивая свой предельный продукт капитала с его стоимостью.

Когда предельный продукт капитала выше стоимости капитала, имеет смысл увеличить производство путем увеличения капитала, но как только предельный продукт капитала падает ниже стоимости капитала, добавление еще большего капитала приводит к уменьшению прибыли фирмы.

Совокупное производство экономики в большинстве случаев лучше всего представлено производственной функцией Кобба-Дугласа с постоянным эффектом масштаба.

Согласно модели Кобба-Дугласа, общее производство экономики (Y) зависит от ее общей факторной производительности (A), запаса рабочей силы (L) и капитала (K), а также от способности Y реагировать на каждый входной сигнал:

Y = A × Kα × L1-α, где

α представляет собой долю капитала, а 1-α представляет собой долю труда, необходимого для производства.

Когда экономика имеет постоянную отдачу от масштаба, любое увеличение капитала при сохранении постоянной рабочей силы приводит к уменьшению предельного продукта капитала, как показано в приведенном ниже примере.

Расчет

Предельный продукт капитала экономики, представленный производственной функцией Кобба-Дугласа, можно рассчитать по следующей формуле:

MPK = α × A × Kα-1 × L1-α = α × (Y / K)

Приведенные выше уравнения выводятся путем дифференцирования функции Кобба-Дугласа относительно K, сохраняя L постоянным.

MPK = ∂Y/∂K = ∂AKαL1-α/∂K

MPK = α × AKα-1L1-α

Перемещение Ка-1 к знаменателю дает нам следующее выражение:

MPK = α × A × (L1-α / K1-α)

Умножив и разделив правую часть приведенного выше уравнения на Ka, получим:

MPK = α × A × (L1-α / K1-α) × (Kα / Kα)

Небольшая перестановка:

MPK = α × [(A × Kα × L1-α) / K1-α+ α)]

Числитель точно равен Y, а знаменатель сводится к K:

MPK = α × (Y / K)

Пример и график

Давайте рассмотрим экономику, которая производит только детские коляски и чье производство представлено следующим уравнением:

Y = 2,000 × K0,5 × L0,5

В следующей таблице показано общее количество детских колясок, произведенных при увеличении числа производственных предприятий, но при этом количество обученных работников, способных управлять ими, остается постоянным.

| Количество заводов | Количество рабочих | Общее производство | Предельный продукт |

| 0 | 500 | – | – |

| 1 | 500 | 44,721 | 44,721 |

| 2 | 500 | 63,246 | 18,524 |

| 3 | 500 | 77,460 | 14,214 |

| 4 | 500 | 89,443 | 11,983 |

| 5 | 500 | 100,000 | 10,557 |

| 6 | 500 | 109,545 | 9,545 |

| 7 | 500 | 118,322 | 8,777 |

На следующей диаграмме показано общее производство (L) по оси Y и капитал (K) по оси X.

Общая кривая производства становится более плоской по мере того, как прибавляется все больше и больше капитала при сохранении постоянной рабочей силы.

Это происходит потому, что когда капитал увеличивается без связанного с ним увеличения рабочей силы, не хватает людей, чтобы управлять машинами, и поэтому рост производства ниже.