Характеристики планет Солнечной системы были известны еще в средневековье, во времена Кеплера и Галилея. То есть, массу планет приблизительно можно было определить даже простыми методами и инструментами. В современной астрономии есть несколько методов расчета характеристик планет, звезд, скоплений и галактик.

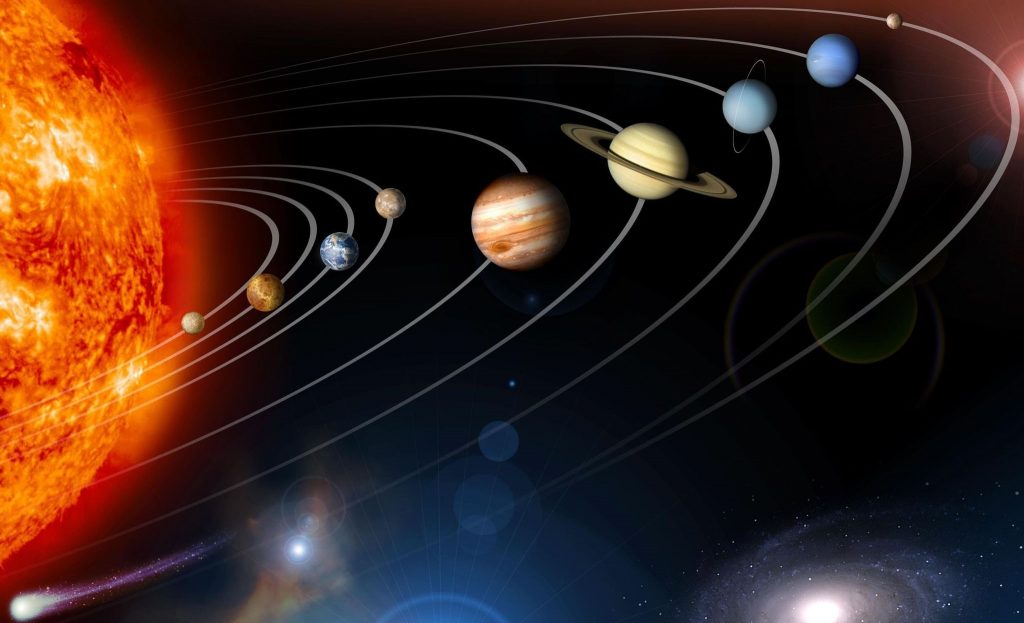

Планеты солнечной системы

Интересный факт: 99,9% всей массы Солнечной системы сосредоточена в самом Солнце. На все планеты вместе взятые приходится не более 0,01%. При этом из этих 0,01%, в свою очередь, 99% массы приходится на газовые гиганты (в том числе 90% только на Юпитер и Сатурн).

Содержание:

- 1 Рассчитываем массу Земли и Луны

- 2 Общие методики определения масс планет

- 3 Значения масс планет Солнечной системы

- 4 Определение масс звезд и галактик

Рассчитываем массу Земли и Луны

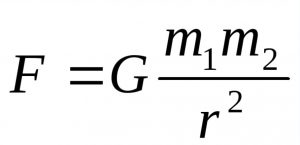

Чтобы измерить массу планет солнечной системы, проще всего в первую очередь найти значения для Земли. Как мы помним, ускорение свободного падения определяется по формуле F=mg, где m – масса тела, а F – действующая на него сила.

Параллельно вспоминаем универсальный закон всемирного тяготения Ньютона:

Сопоставив эти две формулы, и зная значение гравитационной постоянной 6,67430(15)·10−11 м³/(кг·с²), можно рассчитать массу Земли. Ускорение свободного падения на Земле мы знаем, 9,8 м/с2, радиус планеты тоже. Подставив все данные на выходе получим приблизительно 5,97 х 10²⁴ кг.

Земля и луна

Зная массу Земли, мы легко рассчитает параметры по другим объектам Солнечной системы – Луна, планеты, Солнце и так далее. С Луной вообще все довольно просто. Здесь достаточно учесть, что расстояния от центров тел до центра масс соотносятся обратно их массам. Подставив эти цифры для Земли и ее спутника получим массу Луны 7.36 × 10²² килограмма.

Перейдем теперь к методикам измерения массы планет земной группы – Меркурий, Венера, Марс. После чего рассмотрим газовые гиганты, и в самом конце – экзопланеты, звезды и галактики.

Общие методики определения масс планет

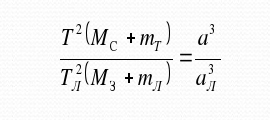

Наиболее классический способ, как узнать массу планет – расчет при помощи формул третьего закона Кеплера. Он гласит, что квадраты периодов обращения планет соотносятся так же, как кубы больших полуосей орбит. Ньютон немного уточнил этот закон, внеся в формулу массы небесных тел. На выходе получилась такая формула –

Таким способом можно найти массу всех планет Солнечной системы и самого Солнца.И периоды обращения, и большие полуоси орбит планет Солнечной системы легко измеряются астрономическими методиками, доступными даже без сложных инструментов. А так как массу Земли мы уже рассчитали, можно все цифры подставить в формулу и найти конечный результат.

В отношении же экзопланет и других звезд (но только двойных) в астрономии обычно применяется метод анализа видимых возмущений и колебаний. Он основан на том факте, что все массивные тела “возмущают” орбиты друг друга.

Такими расчетами были открыты планеты Нептун и Плутон, еще до их визуального обнаружения, как говорят “на кончике пера”.

Значения масс планет Солнечной системы

Итак, мы разобрались с общими методиками расчета масс разных небесных тел и посчитали значения для Луны, Земли и Галактики. Давайте теперь составим рейтинг планет нашей системы по их массе.

Возглавляет рейтинг с наибольшей массой планет Солнечной системы – Юпитер, которому не хватило одного порядка чтобы наша система стала двойной. Еще чуть-чуть и у нас могло быть два Солнца, второе вместо Юпитера. Итак, масса этого газового гиганта равняется 1,9 × 10²⁷ кг.

Интересно, что Юпитер – единственная планета нашей системы, центр масс вращения с Солнцем которой расположен вне поверхности звезды. Он отстоит примерно на 7% расстояния между ними от поверхности Солнца.

Вторая по массе планета – Сатурн, его масса 5,7 × 10²⁶ кг. Следующим идет Нептун – 1 × 10²⁶. Четвёртая по массе планета, газовый гигант Уран, масса которого – 8,7 × 10²⁵ кг.

Далее идут планеты земной группы, каменистые тела, в отличие от газовых гигантов с их большим радиусом и относительно малой плотностью.

Определение масс звезд и галактик

Для того чтобы найти характеристики одинарных звездных систем применяется гравиметрический метод. Его суть в измерении гравитационного красного смещения света звезды. Оно измеряется по формуле ∆V=0,635 M/R, где M и R – масса и радиус звезды, соответственно.

Косвенно можно также вычислить массу звезды по видимому спектру и светимости. Сначала определяется ее класс светимости по диаграмме Герцшпрунга-Рассела, а потом вычисляется зависимость масса/светимость. Такой способ не подходит для белых карликов и нейтронных звезд.

Масса галактик вычисляется в основном по скорости вращения ее звезд (или просто по относительной скорости звезд, если это не спиральная галактика). Все тот же всемирный закон тяготения Ньютона нам гласит, что центробежную силу звезд в галактике можно выразить в формуле:

Только в этот раз в формулу мы подставляем расстояние от Солнца до центра нашей галактики и его массу. Так можно рассчитать массу Млечного Пути, которая равняется 2,2 × 10⁴⁴г.

Не забываем, что эта цифра – это масса галактики без учета звезд, орбиты которых располагаются вне орбиты вращения Солнца. Поэтому для более точных расчетов берутся самые внешние звезды рукавов спиральных галактик.

Для эллиптических галактик способ нахождения массы схож, только там берется зависимость между угловым размером, скоростью движения звезд и общей массой.

Тут народ вполне грамотно изложил, на основе каких законов это делали, но недостаточно подробно рассказал, как именно. Попробую восполнить досадный пробел.

Да, законы Кеплера и закон всемирного тяготения (который Ньютон открыл вовсе не из-за яблока, а стараясь найти математическое обоснование законам Кеплера).

Смотрите: из закона всемирного тяготения следует и связь параметров орбиты спутника с массой небесного тела, вокруг которого он вращается. Да даже и спутника не надо — вот тупо ускорение свободного падения напрямую связано с массой Земли и её радиусом: g = GM/R², где G — коэффициент пропорциональности из закона всемирного тяготения, он же гравитационная постоянная. Радиус Земли научились определять ещё в древней Греции, так что из значения g и известного радиуса R выползается и М. Если же вернуться к системе тел, например, Солнечной системе, то из параметров орбиты Земли можно вычислить массу Солнца. Скорость, с которой Земля движется вокруг Солнца, равна корню из GMₑRₑ (Mₑ и Rₑ — это соответственно масса Солнца и радиус орбиты Земли, если считать её круговой).

Так вот, параметры земной орбиты, как и параметры лунной орбиты, умели достаточно точно определять уже во времена Ньютона. Значит, вся сложность тут — в измерении значения гравитационной постоянной. Первым её измерил английский физик Кэвендиш. Ну собсно всё — как только стало известным значение G, не составило труда вычислить массу Земли и массу Солнца.

Массы планет вычисляются весьма просто, если у планеты есть спутники. Тут ровно то же самое. Параметры орбиты спутника измеряются непосредственно. И точно так же, по формуле первой космической скорости, из параметров орбиты вычисляется масса планеты.

С планетами, у которых спутников нет (не повезло в этом плане Меркурию и Венере), пришлось, как тут уже опомянуто, внимательно анализировать возмущения, которые их движение оказывает на соседей. То есть Меркурий до некоторой степени выступает «спутником» Венеры, и по тому, как Венера влияет на параметры орбиты Меркурия (и, разумеется, с учётом влияния всех прочих планет), как именно орбита Меркурия отклоняется от идеальной, которой она была бы в отсутствие влияния других планет, вычисляется масса влияющей планеты.

Масса других звёзд определяется примерно так же, но не для всех. Для начала сумели определить массу звёзд, входящих в кратные системы (Двойные, тройные и т. д.). Раз есть два тела, и раз расстояние между ними известно — опять же из прямых астрономических наблюдений, — то из этого расстояния и периода обращения немедленно вычисляются массы компонентов.

А вот дальше сложнее. Ну окей, большинство звёзд — примерно 70% — действительно въодят в кратные системы. А как быть с одиночными звёздами?

А просто. Как показала статистика измерений массы звёзд из кратных систем, оная масса довольно тесно связана со светимостью звезды и с её спектральным классом (диаграмма Герцшпрунга-Рассела). Чем выше светимость звезды, тем она массивнее. Вот эта диаграмма и позволяет весьма достоверно оценить — не измерить, а именно оценить, предсказать, — массу одиночной звезды по спектру излучаемого ею света.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In astronomy, planetary mass is a measure of the mass of a planet-like astronomical object. Within the Solar System, planets are usually measured in the astronomical system of units, where the unit of mass is the solar mass (M☉), the mass of the Sun. In the study of extrasolar planets, the unit of measure is typically the mass of Jupiter (MJ) for large gas giant planets, and the mass of Earth (MEarth) for smaller rocky terrestrial planets.

The mass of a planet within the Solar System is an adjusted parameter in the preparation of ephemerides. There are three variations of how planetary mass can be calculated:

- If the planet has natural satellites, its mass can be calculated using Newton’s law of universal gravitation to derive a generalization of Kepler’s third law that includes the mass of the planet and its moon. This permitted an early measurement of Jupiter’s mass, as measured in units of the solar mass.

- The mass of a planet can be inferred from its effect on the orbits of other planets. In 1931-1948 flawed applications of this method led to incorrect calculations of the mass of Pluto.

- Data from influence collected from the orbits of space probes can be used. Examples include Voyager probes to the outer planets and the MESSENGER spacecraft to Mercury.

- Also, numerous other methods can give reasonable approximations. For instance, Varuna, a potential dwarf planet, rotates very quickly upon its axis, as does the dwarf planet Haumea. Haumea has to have a very high density in order not to be ripped apart by centrifugal forces. Through some calculations, one can place a limit on the object’s density. Thus, if the object’s size is known, a limit on the mass can be determined. See the links in the aforementioned articles for more details on this.

Choice of units[edit]

The choice of solar mass, M☉, as the basic unit for planetary mass comes directly from the calculations used to determine planetary mass. In the most precise case, that of the Earth itself, the mass is known in terms of solar masses to twelve significant figures: the same mass, in terms of kilograms or other Earth-based units, is only known to five significant figures, which is less than a millionth as precise.[1]

The difference comes from the way in which planetary masses are calculated. It is impossible to «weigh» a planet, and much less the Sun, against the sort of mass standards which are used in the laboratory. On the other hand, the orbits of the planets give a great range of observational data as to the relative positions of each body, and these positions can be compared to their relative masses using Newton’s law of universal gravitation (with small corrections for General Relativity where necessary). To convert these relative masses to Earth-based units such as the kilogram, it is necessary to know the value of the Newtonian constant of gravitation, G. This constant is remarkably difficult to measure in practice, and its value is only known to a precision of one part in ten-thousand.[2]

The solar mass is quite a large unit on the scale of the Solar System: 1.9884(2)×1030 kg.[1] The largest planet, Jupiter, is 0.09% the mass of the Sun, while the Earth is about three millionths (0.0003%) of the mass of the Sun. Various different conventions are used in the literature to overcome this problem: for example, inverting the ratio so that one quotes the planetary mass in the ‘number of planets’ it would take to make up one Sun.[1] Here, we have chosen to list all planetary masses in ‘microSuns’ – that is the mass of the Earth is just over three ‘microSuns’, or three millionths of the mass of the Sun – unless they are specifically quoted in kilograms.

When comparing the planets among themselves, it is often convenient to use the mass of the Earth (ME or MEarth) as a standard, particularly for the terrestrial planets. For the mass of gas giants, and also for most extrasolar planets and brown dwarfs, the mass of Jupiter (MJ) is a convenient comparison.

| Planet | Mercury | Venus | Earth | Mars | Jupiter | Saturn | Uranus | Neptune |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth mass MEarth | 0.0553 | 0.815 | 1 | 0.1075 | 317.8 | 95.2 | 14.6 | 17.2 |

| Jupiter mass MJ | 0.000 17 | 0.002 56 | 0.003 15 | 0.000 34 | 1 | 0.299 | 0.046 | 0.054 |

Planetary mass and planet formation[edit]

Vesta is the second largest body in the asteroid belt after Ceres. This image from the Dawn spacecraft shows that it is not perfectly spherical.

The mass of a planet has consequences for its structure by having a large mass, especially while it is in the hand of process of formation. A body with enough mass can overcome its compressive strength and achieve a rounded shape (roughly hydrostatic equilibrium). Since 2006, these objects have been classified as dwarf planet if it orbits around the Sun (that is, if it is not the satellite of another planet). The threshold depends on a number of factors, such as composition, temperature, and the presence of tidal heating. The smallest body that is known to be rounded is Saturn’s moon Mimas, at about 1⁄160000 the mass of Earth; on the other hand, bodies as large as the Kuiper belt object Salacia, at about 1⁄13000 the mass of Earth, may not have overcome their compressive strengths. Smaller bodies like asteroids are classified as «small Solar System bodies».

A dwarf planet, by definition, is not massive enough to have gravitationally cleared its neighbouring region of planetesimals. The mass needed to do so depends on location: Mars clears its orbit in its current location, but would not do so if it orbited in the Oort cloud.

The smaller planets retain only silicates and metals, and are terrestrial planets like Earth or Mars. The interior structure of rocky planets is mass-dependent: for example, plate tectonics may require a minimum mass to generate sufficient temperatures and pressures for it to occur.[3] Geophysical definitions would also include the dwarf planets and moons in the outer Solar System, which are like terrestrial planets except that they are composed of ice and rock rather than rock and metal: the largest such bodies are Ganymede, Titan, Callisto, Triton, and Pluto.

If the protoplanet grows by accretion to more than about twice the mass of Earth, its gravity becomes large enough to retain hydrogen in its atmosphere. In this case, it will grow into an ice giant or gas giant. As such, Earth and Venus are close to the maximum size a planet can usually grow to while still remaining rocky.[4] If the planet then begins migration, it may move well within its system’s frost line, and become a hot Jupiter orbiting very close to its star, then gradually losing small amounts of mass as the star’s radiation strips its atmosphere.

The theoretical minimum mass a star can have, and still undergo hydrogen fusion at the core, is estimated to be about 75 MJ, though fusion of deuterium can occur at masses as low as 13 Jupiters.[5][6][7]

Values from the DE405 ephemeris[edit]

The DE405/LE405 ephemeris from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory[1][8] is a widely used ephemeris dating from 1998 and covering the whole Solar System. As such, the planetary masses form a self-consistent set, which is not always the case for more recent data (see below).

| Planets and natural satellites |

Planetary mass (relative to the Sun × 10−6 ) |

Satellite mass (relative to the parent planet) |

Absolute mass |

Mean density |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.16601 | 3.301×1023 kg | 5.43 g/cm3 | ||

| Venus | 2.4478383 | 4.867×1024 kg | 5.24 g/cm3 | ||

| Earth/Moon system | 3.04043263333 | 6.046×1024 kg | 4.4309 g/cm3 | ||

| Earth | 3.00348959632 | 5.972×1024 kg | [a] 5.514 g/cm3 | ||

| Moon | 1.23000383×10−2 | 7.348×1022 kg | [a] 3.344 g/cm3 | ||

| Mars | 0.3227151 | 6.417×1023 kg | 3.91 g/cm3 | ||

| Jupiter | 954.79194 | 1.899×1027 kg | 1.24 g/cm3 | ||

| Io | 4.70×10−5 | 8.93×1022 kg | |||

| Europa | 2.53×10−5 | 4.80×1022 kg | |||

| Ganymede | 7.80×10−5 | 1.48×1023 kg | |||

| Callisto | 5.67×10−5 | 1.08×1023 kg | |||

| Saturn | 285.8860 | 5.685×1026 kg | 0.62 g/cm3 | ||

| Titan | 2.37×10−4 | 1.35×1023 kg | |||

| Uranus | 43.66244 | 8.682×1025 kg | 1.24 g/cm3 | ||

| Titania | 4.06×10−5 | 3.52×1021 kg | |||

| Oberon | 3.47×10−5 | 3.01×1021 kg | |||

| Neptune | 51.51389 | 1.024×1026 kg | 1.61 g/cm3 | ||

| Triton | 2.09×10−4 | 2.14×1022 kg | |||

| Dwarf planets and asteroids | |||||

| Pluto/Charon system | 0.007396 | 1.471×1022 kg | 2.06 g/cm3 | ||

| Ceres | 0.00047 | 9.3×1020 kg | |||

| Vesta | 0.00013 | 2.6×1020 kg | |||

| Pallas | 0.00010 | 2.0×1020 kg |

Earth mass and lunar mass[edit]

Where a planet has natural satellites, its mass is usually quoted for the whole system (planet + satellites), as it is the mass of the whole system which acts as a perturbation on the orbits of other planets. The distinction is very slight, as natural satellites are much smaller than their parent planets (as can be seen in the table above, where only the largest satellites are even listed).

The Earth and the Moon form a case in point, partly because the Moon is unusually large (just over 1% of the mass of the Earth) in relation to its parent planet compared with other natural satellites. There are also very precise data available for the Earth–Moon system, particularly from the Lunar Laser Ranging experiment (LLR).

The geocentric gravitational constant – the product of the mass of the Earth times the Newtonian constant of gravitation – can be measured to high precision from the orbits of the Moon and of artificial satellites. The ratio of the two masses can be determined from the slight wobble in the Earth’s orbit caused by the gravitational attraction of the Moon.

More recent values[edit]

The construction of a full, high-precision Solar System ephemeris is an onerous task.[9] It is possible (and somewhat simpler) to construct partial ephemerides which only concern the planets (or dwarf planets, satellites, asteroids) of interest by «fixing» the motion of the other planets in the model. The two methods are not strictly equivalent, especially when it comes to assigning uncertainties to the results: however, the «best» estimates – at least in terms of quoted uncertainties in the result – for the masses of minor planets and asteroids usually come from partial ephemerides.

Nevertheless, new complete ephemerides continue to be prepared, most notably the EPM2004 ephemeris from the Institute of Applied Astronomy of the Russian Academy of Sciences. EPM2004 is based on 317014 separate observations between 1913 and 2003, more than seven times as many as DE405, and gave more precise masses for Ceres and five asteroids.[9]

| EPM2004[9] | Vitagliano & Stoss (2006)[10] |

Brown & Schaller (2007)[11] |

Tholen et al. (2008)[12] |

Pitjeva & Standish (2009)[13] |

Ragozzine & Brown (2009)[14] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 136199 Eris | 84.0(1.0)×10−4 | |||||

| 134340 Pluto | 73.224(15)×10−4 [b] | |||||

| 136108 Haumea | 20.1(2)×10−4 | |||||

| 1 Ceres | 4.753(7)×10−4 | 4.72(3)×10−4 | ||||

| 4 Vesta | 1.344(1)×10−4 | 1.35(3)×10−4 | ||||

| 2 Pallas | 1.027(3)×10−4 | 1.03(3)×10−4 | ||||

| 15 Eunomia | 0.164(6)×10−4 | |||||

| 3 Juno | 0.151(3)×10−4 | |||||

| 7 Iris | 0.063(1)×10−4 | |||||

| 324 Bamberga | 0.055(1)×10−4 |

IAU best estimates (2009)[edit]

A new set of «current best estimates» for various astronomical constants[15] was approved the 27th General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in August 2009.[16]

| Planet | Ratio of the solar mass to the planetary mass (including satellites) |

Planetary mass (relative to the Sun × 10−6) |

Mass (kg) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 6023.6(3)×103 | 0.166014(8) | 3.3010(3)×1023 | [17] |

| Venus | 408.523719(8)×103 | 2.08106272(3) | 4.1380(4)×1024 | [18] |

| Mars | 3098.70359(2)×103 | 0.3232371722(21) | 6.4273(6)×1023 | [19] |

| Jupiter[c] | 1.0473486(17)×103 | 954.7919(15) | 1.89852(19)×1027 | [20] |

| Saturn | 3.4979018(1)×103 | 285.885670(8) | 5.6846(6)×1026 | [21] |

| Uranus | 22.90298(3)×103 | 43.66244(6) | 8.6819(9)×1025 | [22] |

| Neptune | 19.41226(3)×103 | 51.51384(8) | 1.02431(10)×1026 | [23] |

IAU current best estimates (2012)[edit]

The 2009 set of «current best estimates» was updated in 2012 by resolution B2 of the IAU XXVIII General Assembly.

[24]

Improved values were given for Mercury and Uranus (and also for the Pluto system and Vesta).

| Planet | Ratio of the solar mass to the planetary mass (including satellites) |

|---|---|

| Mercury | 6023.657 33 (24)×103 |

| Uranus | 22.902951(17)×103 |

See also[edit]

- Astronomical system of units

- Standard gravitational parameter

- Planetary-mass object

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b The separate densities given for the Earth and Moon were not determined from the DE405/LE405 data, but are listed in the table for comparison to other planets and satellites.

- ^ For ease of comparison with other values, the mass given in the table is for the entire Pluto system: this is also the value which appears in the IAU «current best estimates». Tholen et al. also give estimates for the masses of the four bodies which comprise the Pluto system: Pluto 6.558(28)×10−9 M☉, 1.304(5)×1022 kg; Charon 7.64(21)×10−10 M☉, 1.52(4)×1021 kg; Nix 2.9×10−13 M☉, 5.8×1017 kg; Hydra 1.6×10−13 M☉, 3.2×1017 kg.

- ^ The value quoted by the IAU Working Group on Numerical Standards for Fundamental Astronomy (1.047348644×103) is inconsistent with the quoted uncertainty (1.7×10−3): the value has been rounded here.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d «2009 Selected Astronomical Constants Archived 2009-03-27 at the Wayback Machine» in «The Astronomical Almanac Online». USNO, UKHO.

- ^ Mohr, Peter J.; Taylor, Barry N.; Newell, David B. (2008). «CODATA Recommended Values of the Fundamental Physical Constants: 2006» (PDF). Reviews of Modern Physics. 80 (2): 633–730. arXiv:0801.0028. Bibcode:2008RvMP…80..633M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.80.633. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-01.

Direct link to value.. - ^ CfA Press Release Release No.: 2008-02 January 09, 2008 Earth: A Borderline Planet for Life?

- ^ Chen, Jingjing; Kipping, David (2016). «Probabilistic Forecasting of the Masses and Radii of Other Worlds». The Astrophysical Journal. 834 (1): 17. arXiv:1603.08614. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/834/1/17. S2CID 119114880. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Boss, Alan (2001-04-03). «Are they planets or what?». Carnegie Institution of Washington. Archived from the original on 2006-09-28. Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ^ Shiga, David (2006-08-17). «Mass cut-off between stars and brown dwarfs revealed». New Scientist. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ Basri, Gibor (2000). «Observations of Brown Dwarfs». Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 38: 485. Bibcode:2000ARA&A..38..485B. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.38.1.485.

- ^ Standish, E. M. (1998). «JPL Planetary and Lunar Ephemerides, DE405/LE405» (PDF). JPL IOM 312.F-98-048. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-29.

- ^ a b c Pitjeva, E.V. (2005). «High-Precision Ephemerides of Planets—EPM and Determination of Some Astronomical Constants» (PDF). Solar System Research. 39 (3): 176–86. Bibcode:2005SoSyR..39..176P. doi:10.1007/s11208-005-0033-2. S2CID 120467483. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-22.

- ^ Vitagliano, A.; Stoss, R. M. (2006). «New mass determination of (15) Eunomia based on a very close encounter with (50278) 2000CZ12». Astron. Astrophys. 455 (3): L29–31. Bibcode:2006A&A…455L..29V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20065760..

- ^ Brown, Michael E.; Schaller, Emily L. (15 June 2007). «The Mass of Dwarf Planet Eris». Science. 316 (5831): 1585. Bibcode:2007Sci…316.1585B. doi:10.1126/science.1139415. PMID 17569855. S2CID 21468196.

- ^ Tholen, David J.; Buie, Marc W.; Grundy, William M.; Elliott, Garrett T. (2008). «Masses of Nix and Hydra». Astron. J. 135 (3): 777–84. arXiv:0712.1261. Bibcode:2008AJ….135..777T. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/135/3/777. S2CID 13033521..

- ^ Pitjeva, E. V.; Standish, E. M. (2009). «Proposals for the masses of the three largest asteroids, the Moon-Earth mass ratio and the Astronomical Unit». Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron. 103 (4): 365–72. Bibcode:2009CeMDA.103..365P. doi:10.1007/s10569-009-9203-8. S2CID 121374703..

- ^ Ragozzine, Darin; Brown, Michael E. (2009). «Orbits and Masses of the Satellites of the Dwarf Planet Haumea = 2003 EL61». Astron. J. 137 (6): 4766–76. arXiv:0903.4213. Bibcode:2009AJ….137.4766R. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/6/4766. S2CID 15310444..

- ^ IAU WG on NSFA Current Best Estimates (Report). Archived from the original on December 8, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

- ^ «The final session of the [IAU] General Assembly» (PDF). Estrella d’Alva. 2009-08-14. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06..

- ^ Anderson, John D.; Colombo, Giuseppe; Esposito, Pasquale B.; Lau, Eunice L.; et al. (1987). «The Mass Gravity Field and Ephemeris of Mercury». Icarus. 71 (3): 337–49. Bibcode:1987Icar…71..337A. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(87)90033-9..

- ^ Konopliv, A. S.; Banerdt, W. B.; Sjogren, W. L. (1999). «Venus Gravity: 180th Degree and Order Model». Icarus. 139 (1): 3–18. Bibcode:1999Icar..139….3K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.524.5176. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6086..

- ^ Konopliv, Alex S.; Yoder, Charles F.; Standish, E. Myles; Yuan, Dah-Ning; et al. (2006). «A global solution for the Mars static and seasonal gravity, Mars orientation, Phobos and Deimos masses, and Mars ephemeris». Icarus. 182 (1): 23–50. Bibcode:2006Icar..182…23K. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2005.12.025..

- ^ Jacobson, R. A.; Haw, R. J.; McElrath, T. P.; Antreasian, P. G. (2000). «A Comprehensive Orbit Reconstruction for the Galileo Prime Mission in the J2000 System». Journal of the Astronautical Sciences. 48 (4): 495–516. doi:10.1007/BF03546268. hdl:2060/20000056904..

- ^ Jacobson, R. A.; Antreasian, P. G.; Bordi, J. J.; Criddle, K. E.; et al. (2006). «The gravity field of the Saturnian system from satellite observations and spacecraft tracking data». Astron. J. 132 (6): 2520–26. Bibcode:2006AJ….132.2520J. doi:10.1086/508812..

- ^ Jacobson, R. A.; Campbell, J. K.; Taylor, A. H.; Synott, S. P. (1992). «The Masses of Uranus and its Major Satellites from Voyager Tracking Data and Earth-based Uranian Satellite Data». Astron. J. 103 (6): 2068–78. Bibcode:1992AJ….103.2068J. doi:10.1086/116211..

- ^ Jacobson, R. A. (3 April 2009). «The Orbits of the Neptunian Satellites and the Orientation of the Pole of Neptune». The Astronomical Journal. 137 (5): 4322–4329. Bibcode:2009AJ….137.4322J. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/137/5/4322.

- ^ Current Best Estimates (CBEs) (Report). Archived from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2019-06-17.

поделиться знаниями или

запомнить страничку

- Все категории

-

экономические

43,662 -

гуманитарные

33,654 -

юридические

17,917 -

школьный раздел

611,985 -

разное

16,906

Популярное на сайте:

Как быстро выучить стихотворение наизусть? Запоминание стихов является стандартным заданием во многих школах.

Как научится читать по диагонали? Скорость чтения зависит от скорости восприятия каждого отдельного слова в тексте.

Как быстро и эффективно исправить почерк? Люди часто предполагают, что каллиграфия и почерк являются синонимами, но это не так.

Как научится говорить грамотно и правильно? Общение на хорошем, уверенном и естественном русском языке является достижимой целью.